Explorer la gouvernance hybride de l'océan en haute mer pour la mer des Sargasses et le dôme thermal

Le projet de recherche

Le projet “SARGADOM” se concentre sur deux sites remarquables en haute mer : la mer des Sargasses dans l’Atlantique Nord (“SARGA”) et le dôme thermal dans le Pacifique tropical oriental (“DOM”). L’objectif du projet est de contribuer à la protection de la biodiversité et des services écosystémiques, et de faciliter le développement d’approches hybrides de gouvernance de l’océan pour ces deux sites.

–

La mer des Sargasses et le dôme thermal fournissent des exemples de la valeur des écosystèmes de haute mer, tout en mettant en évidence les obstacles à leur protection.

– Français

Événements à venir

et dernières actualités

Actualité

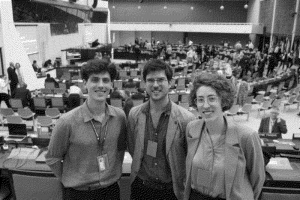

3 observateurs suivent en direct la réunion de l’AIFM

Du 10 au 28 juillet trois chercheurs ont collaboré pour partager leurs observations à la dernière réunion annuelle de l’Autorité internationale des fonds marins

juillet 13, 2023

Actualité

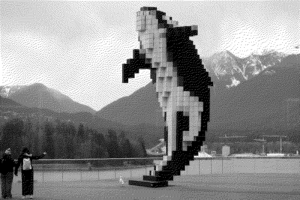

Conférence IMPAC5

La cinquième édition du congrès IMPAC5 dédié aux Aires marines protégées s’est déroulé à Vancouver du 3 au 9 février 2022 sous les auspices de l’UICN.

mars 23, 2023